By Delhi Manipur Society

Myth of the violence: What’s generally perceived?

In the aftermath of the May violence in Manipur, several narratives are in circulation. Several intellectuals and civil society organisations with vested interests have fabricated various narratives in the national and social media, and interpreted the violence as a result of clashes between the tribals and the Meiteis. The objective is to corner the Meiteis and consolidate the tribal (Kuki-Chin-Mizo) voices. The other terms used are ‘Christian Tribal vs. Hindu Meitei’, ‘Hills vs. Valley’, etc. These binaries take the issue far from reality. Therefore, it is important to put the issues in the right perspective. This implies not only putting the facts in order, but also going to the genesis of the violence and revealing the larger story lying beneath.

Protest on ST status

The violence erupted on May 3, 2023, the day the infamous “peace march” was organised by the All Tribal Students Union Manipur (ATSUM), a pro-Kuki association, with the apprehension that Scheduled Tribe (ST) status would be given to the Meiteis. While the peace rally was proposed for all the tribal areas of the state, it took place only in the Kuki dominated district headquarters of Churachandpur, Kangpokpi, and Tengnoupal.

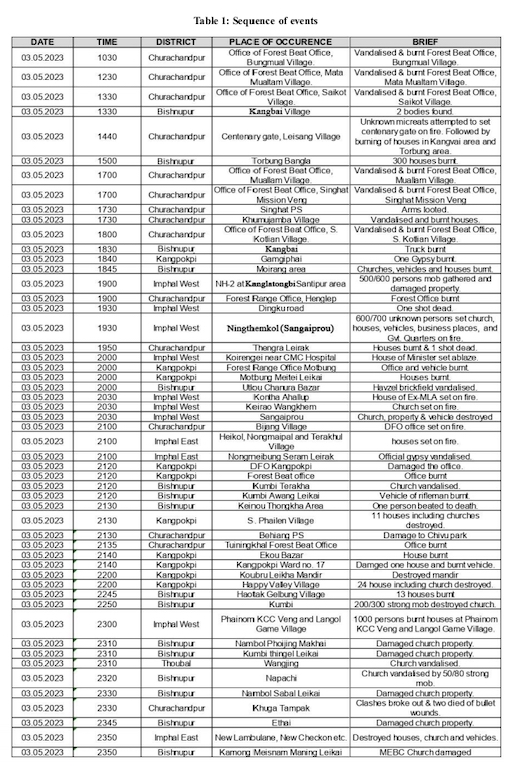

The Kuki militants guarded the peaceful-rally-turned-violent right from the beginning in Churachandpur; forest offices were set on fire as early as 10:30 in the morning. Was the burning of forest offices a manifestation of anger against the state government’s eviction drive of illegal encroachers/immigrants from Reserved Forest (RF) and Protected Forest (PF), Protected Sites, and Wild-Life Sanctuaries? Still, was there any plan to destroy government records on forest areas and settlements?

After a few days, the Manipur Tribal Forum filed a writ petition in the Supreme Court challenging the Manipur High Court order, which directed the state government to expedite its response on the matter of ST reservation for the Meiteis. With the Supreme Court’s intervention, the Manipur High Court has deferred its own decision by one year. It is strange that Kuki civil societies did not exhaust the judicial options to address the issue, which they later did and partially succeeded. Resorting to violence while peaceful means are available shows the character, political disposition, and larger game plan of the Kuki leadership.

It is also hard to digest that a perception of fear would generate such wide-scale violence across the Kuki dominated districts while Naga-dominated districts remain totally peaceful. When such an apprehension was raised, CSOs and Kuki intellectuals made a concerted effort to narrow down the triggering point of violence to an attempted burning of the Kuki Centenary Gate at Leisang Village. While further apprehension was raised, a hit-and-run vehicle driven by a Meitei driver was floated. With events that have unfolded in the last two weeks, it is clear that the anti-ST reservation rally was only a façade that hides several politicalagendasa.

If one has to go into the nomenclature of calling a community in the Northeast either a tribe or a non-tribe, there is lots of arbitrariness. On the Kukis’ objection to including Meiteis in the Scheduled Tribe list of the Indian constitution, the decision on whether Meiteis are backward or not is not to be decided by the contesting communities. There are appropriate forums and institutional bodies that will decide on the matter. Kuki CSOs have failed to abide by those democratic and constitutional means.

Meitei hegemony or Kuki expansionism!

One narrative that is doing the rounds is that of Meitei hegemony in the state. The argument often given is that Manipur is ruled by the Meitei chief minister, and the political representation of valleys and hills is 40:20 ratio. The statement represents a fact, but the underlying spirit is not quite true.

Looking back to the history of Manipur, the spirit with which Manipur has been administered is inclusive and without the dichotomy of tribal vs. non-tribal, or hills vs. valleys. The first chief minister of Manipur after statehood in 1972 was Mohammed Alimuddin, who belonged to the Muslim community (Muslim population then was less than 8% of the total population). He served as chief minister of the state twice. The next chief minister was a tribal leader, Yangmaso Shaiza, who also served as chief minister twice. And the longest serving Chief Minister of Manipur was also a tribal leader Rishang Keishing. The first speaker of Manipur Assembly was T.C. Tiankham, a Kuki tribe. So, the narrative of Meitei domination over political power is a white lie. This fact itself shows that Meiteis believe in plurality of identities and views. None from the majority Meitei community claims exclusive Meitei control over the polity of the State.

As regards the valley–hills ratio, it should be seen as unreserved and reserved seats. The unreserved assembly seats in the valley are 40, and the lone seat in Kangpokpi (hills) district is 1. Any citizen of India can contest these 41 unreserved seats put together. On the other hand, there are 19 reserved assembly seats, which are exclusively to be contested by the tribals.

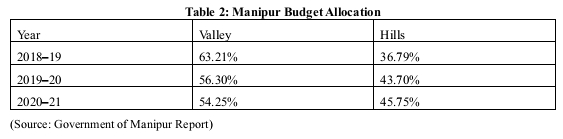

Another myth is that state funds are syphoned off to the valley, whereas the hills are without any developmental works. This, too, is incorrect. A closer look at the Government of Manipur’s budget allocation in the valley and hills in the last few years will set aside the propaganda.

Migration as a cultural phenomenon; brushing aside legality!

Many Kuki scholars have argued that migration is a fact of human reality and that the idea of boundaries is in the communities’ cultural and mental maps. So, to the Kuki-Chin communities, the international boundaries do not make sense; those are always fluid! Their idea of land is driven by cultural imagination and ways of life. This is nothing but trivialising the legitimacy of the modern state and legitimising the notorious nomadic lifestyle of the Kukis. We need to distinctly separate cultural beliefs and worldviews from the legal domain of the modern state structure.

It cannot be denied that the idea of the modern state, articulated through the Westphalian Treaty of 1648, is built on the sovereignty of the state and the legal authority that the state possesses vis-à-vis its citizens and other sovereign states. Weaknesses in the practises of a state cannot be the reason to nullify the presence of the state itself. If the stateis weakk,k it can prevail upon itself to become strong, even to the extent of exercising its legitimate right to assert (and prevail) over its citizens and non-citizens alike. This is the meaning of statesovereignty,ywhicht even the Indian statehass been practising since 1947. It must also be noted that defining and implementing strict international boundaries lies squarely withthe governmentt of India. State governments can only give their inputs, requesting and sharing the concerns and problems faced by the people of the concerned states, the final decision lies with the Indian state.

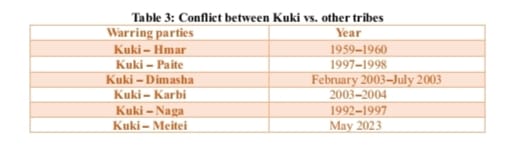

Kukis, being nomadic, do not carry much collective memory. Neither do they have respect for others’ memories. For them, wherever they go becomes their land! To put it simply, their mode of production is built on shifting cultivation. The fertility of the soil shapes their migration pattern. They keep moving from one place to another, continuously breaking themselves into smaller villages. This wandering lifestyle often takes them closer to the habitation of other tribes/communities, thus, leading to friction. Ethnic conflicts between Kukis and other tribes/communities in Manipur and Assam can be witnessed as early as the 1950s. (Today, some of these warring tribes—Kuki, Hmar, and Paite—have joined hands to fight and expel Meiteis from the Kuki dominated region.)

On the other hand, Meiteis and Nagas maintain a close affinity with the land they inhabit. Among the hill tribes, the Nagas are one of the oldest indigenous communities in the Northeast. Their affinity with their land is fixed and sacred; they generally do not infringe on the land inhabited by other communities. This is the characteristic difference between the Kukis and the Nagas.

Meiteis’s association with their land is built on a worldview that is an extension of the body-self. This extension is shaped by the idea of the sacred. Meiteis believe in the eight sacred directions marked by the specific idea of space as frontier. These are also guarded and protected by the respective deities who dwell in the sacred groves. In addition, there are two more directions identified upward (Soraren/ether), and the point where the one stands (the self as the centre). But formidable four directions; viz. South-East, South-West, North-West, and north-east, are marked both by an identified space (mountain in this case) and by associated guardian spirits who protect the land and the people.

The cultural idea of space for the Meiteis is spread over the plains, the hills, and the waterbody. Invoking of the ancestral spirit in Lai Haraoba is built on these spaces. However, today, Meiteis are tied to the valley by the legal discourse of the modern state structure (e.g., MLR&R Act) forbidding them to protect their ancestral sacred sites. Their cultural sites are slowly dwindling.

On the other hand, Kukis have pushed their interests unethically without adhering to any norms. While many Kuki scholars deny the international border between India and Myanmar, highlighting the importance of their lived space and cultural imagination, they conveniently use the Manipur Land Revenue & Reform Act to stop the Meiteis from coming and settling in the hills. They conveniently rely on the modern state structure when it soothes them, and also conveniently use cultural categories in yet another case of their interest. This contradictory political imagination only exhibits hypocrisy and double standards of the highest point.

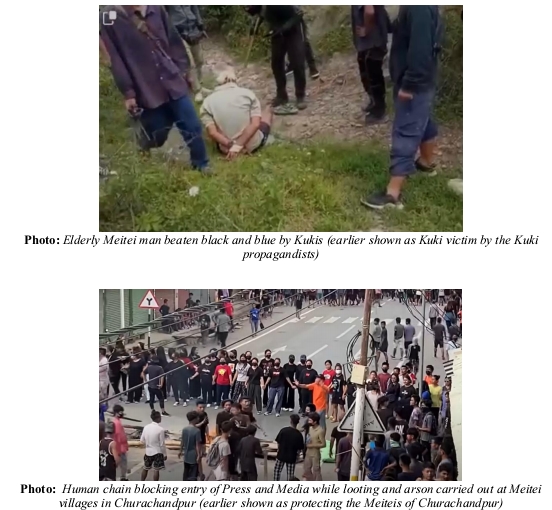

Attack on the churches; but what about the antecedent?

Several seminars are conducted using academic space across the country on Manipur violence. Each of these proceedings does not fail to mention about vandalizing churches in the Imphal valley. While this is an unfortunate turn of events, it was a retaliatory act driven by a violent mob psyche. The anger against the Kuki aggression orchestrated by Kuki militants led to retaliatory consequences that affected Kuki churches. Nevertheless, in the violent act of arson, sanity prevailed, and the Naga churches (also some Kuki churches) were left largely untouched.

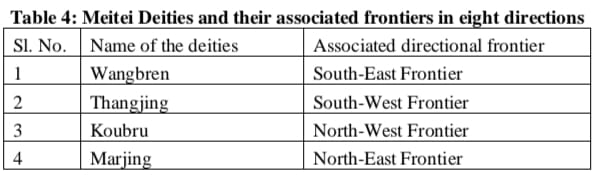

However, these seminars do not inquire into why such unfortunate events have occurred. The antecedent to the church burning lies in a series of events where several Meitei places of worship in the hills (Koubru and Thangjing) were desecrated over a stretch of time. There have been cases where, due to strong resistance by this migrant Kuki population, construction of indigenous temples has stalled in the hill districts. Often these sacred places and associated indigenous practises are treated with contempt and ridicule (the recent case of one Christian pastor, Ramananda, in various church gatherings can be cited). In addition, several armed Kuki militants have been carrying out a series of attacks on the Meitei/Hindu religious shrines and symbols in the past as well as during the recent unrest. A 200-year-old Shiva temple was destroyed using a bulldozer in Koubru Leikha under the Kangpokpi District administration, which is dominated by the Kuki tribes. The local administration turned a blind eye to the whole episode. Contrary to the Meitei unrest, this act shows a well-designed strategy to destroy indigenous places of worship and sacred sites. In addition, the seven-colour flag of the Meiteis has been desecrated by the Kuki militants.

- The reality: Complex linkages

The reality behind the façade of anti-reservation protest lies a web of well-crafted actions by a nexus of Kuki militants, frontal organisations,intellectuals, and politicians. The fact that even after 10 days of violence, several Meitei houses at Torbung Bangla continued to be set on fire by Kuki militants. The reburning happened on 13 May. Even more, two houses were razed to the ground by Kuki militants in Dolaithabi, Imphal East on 20 May. These show not only the quantum of vengeance, but also a well-planned strategy to consolidate Kuki lebensraum (pace sought for occupation by a nation whose population is expanding) in several foothills of the Imphal valley and wipe out the Meiteis from these areas.

It is important to unveil the hidden agenda and the interlinkages of factors that have led to the turmoil experienced today. Nefarious design of the Kuki armed groups, political leaders, bureaucracy, and CSOs need to be unearthed.

Engineered anger against the forest eviction drive

Burning down several forest offices (at Bungmaul Village, Mata Maultam Village, Saikot Village, Maullam Village, Singhat Mission Veng, Kotlian Village, and Henglep) on 3 May 2023 shows that a well-planned and targeted act of burning was engineered by certain stakeholders. Why were only the forest offices targeted? This cannot be without a reason. We cannot rule out any attempt to destroy government records on land and forest areas, as the government had started a drive against forest encroachment by illegal Kuki immigrants.

Not long ago, from 2021–2022, the Government of Manipur initiated a drive for eviction against encroachment on Reserved Forest (RF) and Protected Forest (PF). New constructions at the Langol Reserved Forest in Kangpokpi District were evicted during 2021–2022 in different phases. These encroachers were mostly Meiteis. Eviction of illegal encroachers from RF & PF was also undertaken in April–May 2022 at the Waithou Reserved Forest in Thoubal district in which Meitei and Meitei Pangal encroachers were evicted. In February 2023, 15 temporary Kutcha houses near the National Highway at K. Sonjang Village in Churachandpur– Khoupum Protected Forest (C-KPF) were evicted. It was met with violent resistance from the Myanmar Kuki migrants. On March 10, 2023, the Kuki Student Organisation organised a rally in Kuki dominated areas of Manipur, defying CrPC 144. It was an unlawful gathering. Kuki Inpi, Manipur, also echoed the voice of KSO. Later, the rally extended to New Delhi, where they appealed to the Prime Minister of India to stop the eviction.

On the other hand, the State government issued a clarification stating that K. Sonjang Village was a new settlement established in 2021, much after the notification of the Protected Forest in 1966, and therefore in violation of the Protected Forest Act 1927. However, KSO responded that the notification of 1966 regarding C-KPF with “its allegedly well-defined boundary as unacceptable, illegal and arbitrary in nature as the area covered by the said well- defined boundary is not the property of the State government.” Later it was shown in the media that the drive was targeted exclusively towards the Kuki-Chin-Zo communities.

Considering the above data on the state’s eviction drive, this allegation is far from true. The State government’s drive is not targeted at any specific community. The forest land as “Protected” was declared way before the Kuki migration plagued the entire district of Churachandpur. The eviction drive was part of a larger State policy to protect the RF & PF. On 30 April 2023, Shri Bhupender Yadav, Hon’ble Minister of Labour & Employment, Environment, Forest & Climate Change, Government of India, declared in connection with Manipur government’s drive that “protection of Reserved Forest and Protected Forest is a state subject and that the Manipur Government is carrying out its constitutional duty”. The declaration of KSO is illegal and anti-national. Resorting to violence seems to be the new normal of the Kuki frontal organisation.

It is obvious that affected parties would grumble. However, they could have taken legal options to fight against the State. Unfortunately, many of the tribal communities project the acts of the government on ethnic lines rather than arguing on the merits and demerits of the state policies. The declaration by the 10 Kuki MLAs for a separate administrative arrangement is continuation of this ethnicity-based politics. However, this nefarious design has been challenged by 38 BJP MLAs, consisting of Meiteis, Meitei Pangals (Manipuri Muslims), and the Nagas. Several non-Kuki CSOs have started pouring out against the sinister designs of the Kuki militants. All Zeliangrong Organization (AZO), too, ridiculed the idea of separate administrative arrangement for the Kuki tribes.

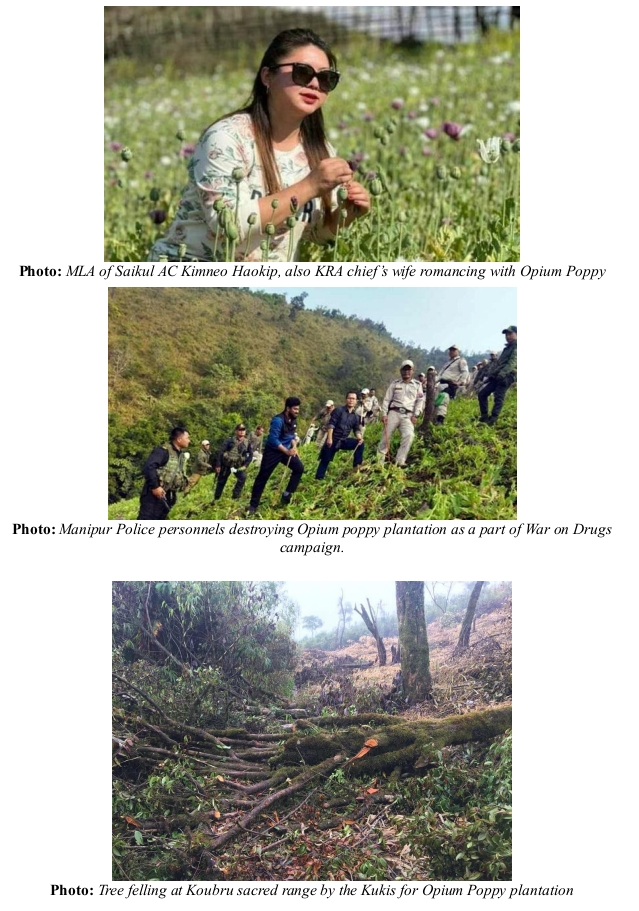

Deforestation and poppy plantations

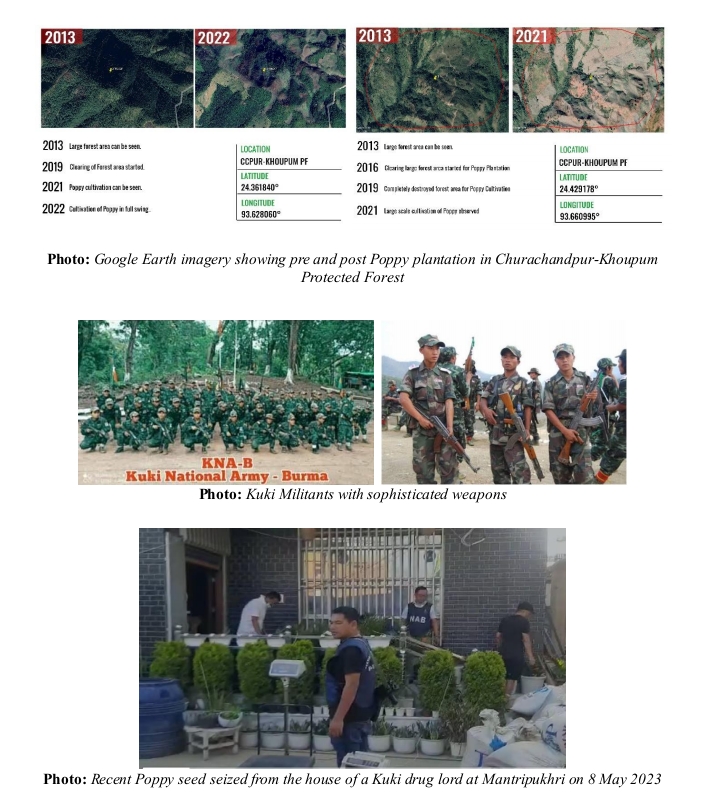

There is a serious need to address the issue of deforestation and environmental imbalances in the region. Due to huge quantities of deforestation (cutting down of timber), the State has witnessed irregular rainfall, changes in temperature, (muddy) flash floods, etc. There is a need to address the issue from the perspective of disaster management.

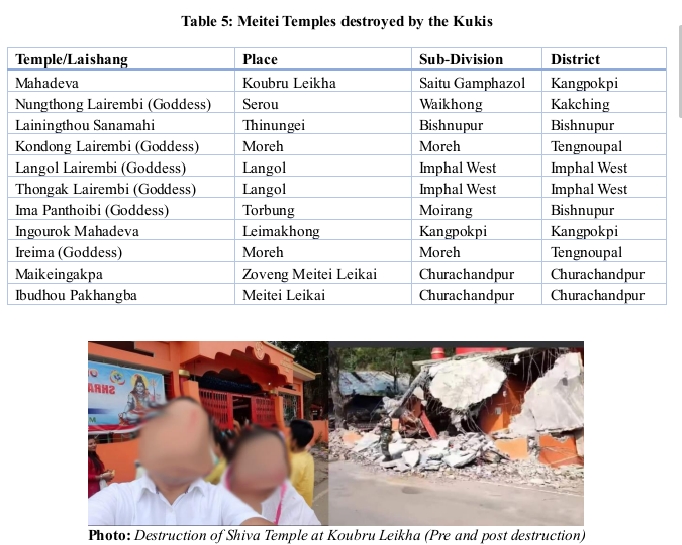

The scenario is further worsened by the rampant massive poppy plantations, particularly in the C-KPF areas, in the past few years, leading to narco-forestation. As per intelligence reports, the Kuki militant groups have been bringing in Chin/Kuki migrants to India. Given basic language classes and military training in their camps, they are settled in the old villages while the villagers of the old villages are shifted to a new village. They are also employing them in poppy fields as well as gun and drug runners.

The State government started a drive against the poppy plantations by destroying the plants at the time of flowering. Since 2017, the government has been able to destroy over 18,000 acres of poppy cultivation, the majority of which are in Kuki dominated districts. This has badly affected the poppy cultivation and narcotics business run by both the local and Myanmarese drug lords in Manipur.

Since the poppy could not be harvested successfully this year due to the crackdown, the drug mafias and the poppy growers have faced heavy financial losses. The anger intensified with the eviction drive by the illegal encroachers from reserved and protected forests. The summation of these factors finally led to ethnic violence. This is planned by groups of people, which include the local and Myanmar-based drug lords, the ‘illegal immigrants’ from Myanmar, and the cross-border terrorist groups.

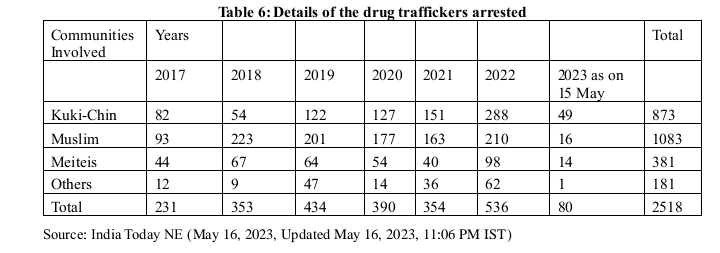

After the Manipur Government launched the War on Drugs in the year 2017, along with the arrest of 2518 people, a total area of 15,496 acres of poppy cultivated land in the hills had been destroyed, in which the Kuki-Chin community recorded significant areas of poppy cultivation, with a total of 13,121.8 acres; the Nagas community reported 2340 acres of poppy cultivation, and other communities accounted for 35 acres only during the period 2017–2023.

It has also been learned that poppy plantations are also rampant in the state of Mizoram.The fact that the Mizoram government is silent about it speaks a ton. It is valid to ask if there is a nefarious nexus between political leadership, armed militants, and drug lords in Mizoram, too. It may also be noted that the poppy cultivators and stakeholders in Mizoram, Churachandpur, Tengnoupal, and Kangpokpi are exclusively tribes of the Kuki-Chin-Mizo fraternity. An underground, illegal, narco-economy is flourishing in this region, which needs to be unearthed and checked. This is a threat to the country’s economy and national security.

Narco-terrorism and threats to national security

There is enough evidence that the armed militants (KNA, ZRA and others), who are under a tripartite ceasefire agreement called “Suspension of Operation” (SoO) with the Government of India and Government of Manipur since 2008, have broken the truce several times. Their involvement in funding the poppy plantation and drug trafficking, threatening the villagers who do not tow their line, and inciting the CSOs to violent protests has led the Government of Manipur to unilaterally break the SoO. Both the armed militants and the migrant populations are a threat to India’s national security. Their involvement in the narcotics business, which in turn funds the arms trade, is of great concern to the entire sub-continent.

It should be noted that the Government of Manipur’s War on Drug campaign could check the narcotic drug business run in the state. The state government has released comprehensive data on the arrests of illicit drug traffickers and the cultivation of poppy during the period 2017–2023. The figures below shed light on the efforts undertaken by the authorities to curb drug-related activities and safeguard the community’s well-being. Arrests under the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (NDPS) Act have been categorised by the community, providing insights into the extent of involvement and the collective responsibility in addressing this issue.

The fact that armed militants (ZRO/KRO) are directly involved in poppy cultivation and drug trafficking is a serious threat to the country’s internal security. Since these groups are under SoO with the Government of India, their movement across the international border between India and Myanmar has remained unchecked. There are reports that these armed militants are expelling the Nepali and Meitei locals from their own villages in Kangpokpi District, where Central paramilitary forces remain mute spectators. Villagers, in frustration, have sought arms to defend themselves since the security forces are not intervening or checking the anti-people activities of the Kuki militants. In short, a complete failure of law and order is witnessed in the Kuki dominated areas. Kuki militants, who are largely Myanmar nationals, are having a great time doing what they want. They have brought their baggage of nefarious lifestyles and converted Manipur into a new ‘golden triangle’.

The issue of narco-terrorism and security threats should be seen as a problem for the entire country and not merely the problem of the Manipur Government. If left unattended, it may lead to irreparable security issues at a later stage.

Aggressive ‘illegal’ migration affecting demographic equilibrium

The Kuki-Chin-Zo population of Myanmar and India, if put together, will outnumber any indigenous population in Manipur. The uninterrupted migration across the border has led to an unnatural surge in the Kuki-Chin-Zo population, thus leading to a demographic imbalance. During the Indian censuses of 1951 and 2011, the Kuki population had risen from 80,002 to 4,48,532. The unnatural growth of the Kuki population during the given period was 3,68,530, which shows almost a five-fold jump in population. This incremental growth cannot be explained through an increase in the birth rate. The obvious factor for this unnatural growth has to be the “illegal” migration. The detection of these alarming numbers of illegal migrants in the first random survey indicates that the total illegal immigrant population from Myanmar into Manipur must be significantly higher than the official figures.

Since India’s independence, there have been broadly three phases of Kuki-Chin-Zo migration into India. The first phase of migration was in the late 1950s and early 1960s, during the civil war in Myanmar. Some of the locations where refugee camps were set up during this time include:

- Tuibong: A town in the Churachandpur district of Manipur.

- Singhat: A town located in the Churachandpur district of Manipur.

- Senvawn: A village located in the Churachandpur district of Manipur.

- Thanlon: A town located in the Churachandpur district of Manipur.

Except for a few, the majority of the refugees did not go back to Myanmar, and there are official communications showing that they were resettled in Manipur by the then Congress Government at the Centre.

The second phase of migration took place before and after the August 8, 1988, uprising in Burma/Myanmar. There were widespread protests and demonstrations against the military Junta government in Myanmar, and several displaced Chin-Kuki people sought refuge in neighbouring countries, including India and Bangladesh. Some of the locations where refugee camps were set up in Manipur during this time include:

- Moreh: A town located on the India-Myanmar border in the Chandel district of Manipur.

- Churachandpur: A town in the Churachandpur district of Manipur.

- Saikul: A town in the Senapati district of Manipur.

The refugees did not go back to Myanmar. The governments of the time (central & state) did not take any steps to deport the large population.

The third phase of migration occurred after the informal ceasefire between the Assam Rifles and Kuki militant groups in 2005, and subsequently after the tripartite Suspension of Operations (SoO) agreement in 2008, where the Government of Manipur, too, got involved. After the informal SoO pact in 2005, Kuki militants stopped attacking the security forces, and the Assam Rifles halted their counter-insurgency operations against the militants. The ceasefire period lasted for about six months. In 2008, 25 Kuki militant groups under two apex militant groups, – Kuki National Organization (KNO) and Zomi Revolutionary Organization (ZRO) entered into a tripartite SoO pact.

The abnormal growth rate of Kuki population in Manipur is also reflected by abnormal increase of new villages in the Kuki dominated districts in Manipur, as evidenced from the Census of India, 1961, to the Census of India, 2021. For example, during the last five decades, in Kangpokpi and Churachandpur districts, where the most violent narco-terrorism is occurring, newly settled villages numbered 355 in Kangpokpi and 262 in Churachandpur. On the other hand, in the Naga dominated districts of Manipur, namely Tamenglong and Senapati, only 42 and 14 new villages have sprung up, respectively. These are strong signs of migrants from outside Manipur, internal and external, having massively settled in Kuki dominated districts.

Due to the recent political crisis of coup and civil war in Myanmar, a significant number of illegal Myanmar nationals belonging to Kuki-Chin-Mizo are entering Manipur. To address national security, the government of Manipur formed a Cabinet Sub-Committee (CSC) led by Minister Letpao Haokip (a Kuki MLA) with the other two ministers. The initial findings of the First Phase of random identification of illegal immigrants in four districts, namely Tengnoupal, Chandel, Churachandpur, and Kamjong, exercised on April 24, 2023, show an alarming presence of illegal migrants from Myanmar. According to a survey, there were 1147 illegal immigrants from Myanmar in Tengnoupal district, bordering Myanmar. Further, the drive also detected 811 illegal Myanmar migrants in Chandel district, 154 Myanmar migrants in Churachandpur district, and 5 Myanmar migrants in Kamjong district. It was found that these illegal migrants established their villages and engaged in different illegal activities.

Effect on Electoral Politics

The new waves of Kuki-Chin-Zo migration in Manipur, Mizoram, and Nagaland (all with an international border with Myanmar) in the last five decades have been the root-cause of the recent crisis. The unnatural population growth geared by waves of illegal migration has led to an increase in the Kuki-Chin population in Manipur. It has also been learned that many of these migrants have also come to Manipur via Mizoram and Nagaland.

Some of these Myanmar nationals procured their Aadhar cards and, subsequently, voter IDs without much difficulty. This is a serious matter. Without a clear national policy on the matter of refugees from other nations, the distinction between the ‘citizen’ and the ‘non-citizen’ becomes blurred. Since the designated camps are not well-regulated, and since the migrants get the support of the earlier migrants and local people, procuring state identification proofs like the Aadhar card and voter ID is often smooth. Thus, they not only avail themselves of Indian citizenship through illegal means, but also join government services, cutting into the opportunities of the locals. Unconfirmed reports state that many of them have gotten high profile jobs in the Central government administration and services. There have been cases of such Myanmar migrants becoming members of various electoral representative bodies both in India and Myanmar. A case of the former Chairman of the Autonomous District Council of Manipur, who was a Myanmar national, and also a political leader in Myanmar, was very much in the local news, but did not gain the attention of the Central government intelligence. Neither the State government intelligence worked on such serious matters. The link between the process of migration, availing of government facilities, and even becoming elected representatives, is a serious matter to be addressed. This corroborates the linkages between foreign migrants, local politicians, money laundering, narco-terrorism, etc.

It goes without saying that these waves of illegal migration are going to affect the process of delimitation, which is already underway. By the 2021 census, the Kuki-Chin-Zo population will have gone up as the second largest population in Manipur, while the Nagas will have been reduced to the third position. This is definitely going to affect electoral politics. The number of unreserved electoral constituencies may get reduced, whereas the number of reserved constituencies in Kuki dominated areas may increase. There are calculations that the number of unreserved constituencies may reduce from 41 to 38, benefiting Kuki representation in the State assembly. This cannot be a coincidence!

Agenda for Kuki–Zomi Homeland

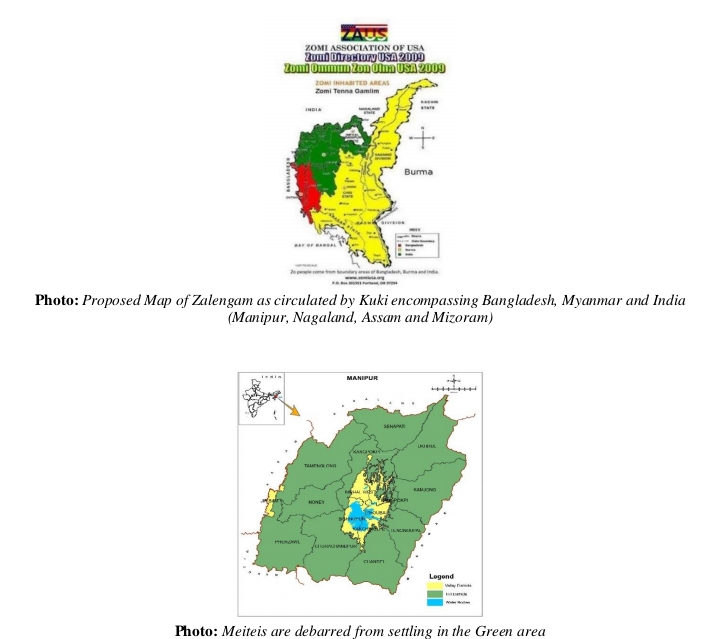

Kuki-Zomi political imagination with a concrete territory is known by several names, such as Zoram, Greater Mizoram, Zalengam, and Kuki homeland. A guarded statement by the Mizoram Manipur Land Revenue and Land Reforms Act 1960 interferes in the internal affairs of Manipur, while talking about greater Mizoram, comes with a rider. The possibility of an ‘indirect’ intervention is not ruled out with his further statement that the hill area of Manipur, adjoining Mizoram, is inhabited by the ‘Zo’ community, who share the same culture, religion, tradition, and ancestry (with the Mizos). The Mizo National Front, to which Zoramthanga is affiliated, fought for an independent Greater Mizoram that ended with bloodshed in 1984. Moreover, the declaration by the 10 Kuki MLAs, currently stationed in Mizoram, for a separate administrative arrangement shows the continuation of a politics based on ethno-nationalism and Mizo hegemony that carries the potential for another round of intra-ethnic conflict within the Chin-Kuki-Mizo group. Their demand aligns with the aim of KNO and ZRO for the self-determination of the Kuki and Zomi people in the form of a defined territory running through India, Myanmar, and Bangladesh.

The idea of a Kuki homeland dates back to the late 1980s, when the Kuki-Zomi insurgent group, the Kuki National Organisation (KNO), came into being. The term ‘Zalengam’ was coined to aspire for a separate Kuki and Zomi homeland. The outbreak of violence in Manipur marks the resurfacing of demand for a separate Kuki administration, which had subsided following peace negotiations between the two militant groups KNO and ZRO with the Indian government under the SoO pact. These two illegal armed outfits have their origins in Myanmar. The leader of KNO PS Haokip, is not originally from Manipur. He was born in Myanmar and brought up in Nagaland.

In 2012, influenced by the demand for a separate Telangana state, an organisation called the Kuki State Demand Committee (KSDC) was formed, and subsequently geared for a movement for Kukiland. KSDC had been calling occasional strikes and economic bandhs even earlier, blocking highways, and not letting goods enter Manipur. The Kuki’s civil society organisations and their armed outfits claim 12,958 sq km, which is more than 60% of Manipur’s 22,000 sq km area to be encompassed for the Zalengam. The claimed territory includes the Sadar Hills (which surround the Imphal valley on three sides), the Kuki-dominated Churachandpur district, Chandel district (which has a mix of Kuki and Naga populations), and even parts of Naga-dominated Tamenglong and Ukhrul. In addition, Mizoram is part of their cartography. Over and above this, they also aspire to include the Chittagong Hills Tract of Bangladesh, and portions of the Chin and Sagaing Divisions of Myanmar.

Kuki homeland narrative is that the tribal areas inhabited by Kuki-Chin-Zomi “are yet to be a part of the Indian Union”. The present chain of violence targeting the Meitei settlements is part of this larger design. The right to self-determination cannot be gained by scuttling the freedom of other communities. Others too have the right to self-determination.

- Is there a way forward?

- Firefighting is the immediate need of the hour. Violence must not escalate; peace must prevail at any cost. Further loss of life and property must be arrested. Control lawlessness; the police must act. Ordinary citizens must once again feel a sense of security.

- Resettlement of communities to their original homes must be ensured. Full security must be provided to the victims, and troublemakers must be strictly dealt with.

- The state must give compensation to all the victims on both sides.

- The government must provide relief measures, and ensure medical facilities for all the victims.

- A full-fledged judicial inquiry must be started under the chairmanship of a Supreme Court judge.

- The Government of India must abrogate the SoO pact with all the Kuki militants, as they are freely moving with arms, and also responsible for inflicting violence on ordinary citizens of this country.

- The NRC must be immediately enacted to detect Myanmar nationals. A special drive must be taken to check the illegal documents they have procured. Those who helped the migrants must be booked.

- The Manipur Land Revenue and Land Reforms Act 1960 must be revisited. Revise it to frame land laws best in the interest of all the communities without comprising equal access and ownership.

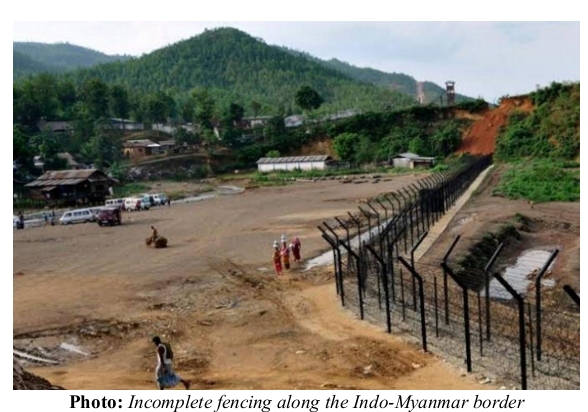

- The Union Government must prioritise border fencing and negotiate with the Myanmar government on regulating cross-border movement.

- There must be a proper policy on refugees. Designated camps must be established to settle the refugees. Absorption of populations from neighbouring countries due to ethnic conflicts, identity politics, or economic and livelihood crises should not be permitted.

- Stability in Manipur can only be sustained by strong, grounded, and all-inclusive social and economic measures that preserve ethnic and demographic balances.