I

“Oksha di nang thongo. Eromba di ei shemke” (You cook pork. I will prepare eromba). Or “Hoksa ina hangkei. Eromba nana semlu” (I will cook pork. You prepare eromba). This could be any random conversation between two friends; a Meitei and a Tangkhul Naga friend getting themselves ready for a grand feast in regional delicacies. This is the common camaraderie and the cultural bonhomie with mutual respect and recognition that Meitei and Tangkhul Nagas share. “Eromba li eromba chirei. Meiteina kasem li mangaphan papam manei”. (“Eromba is eromba. Nothing beats Meiteis in this particular culinary art”). “Kayamuk heidana chekchillaga thongrashu oksha thongbadi ching ki na helle” (“Irrespective of one’s culinary skills and efforts, hill’s ways of cooking is always better when it comes to pork”). As jovial and plain as it sounds, it is as complex as it is simple.

What is so eromba about Meitei eromba? And what is not so eromba about non-Meitei eromba? What is so hoksa about Tangkhul Naga hoksa? And what is not so hoksa about non-Tangkhul Naga hoksa? Hoksa, both for uncooked and cooked pork under different but usually archetypal Tangkhul Naga cuisine, does not confine to Tangkhul Nagas alone but for the sake of convenience in this particular article, may it be allowed to be addressed as Tangkhul Naga hoksa or hoksa as it is also used widely among the Tangkhul Nagas and as this particular debate is not on hoksa.

Meanwhile, controversies surrounding Luirim Kachon as known to Tangkhul Nagas and Leiroom (living together) Phee or Mung Phee (Ruler’s Shawl) to the Meitei community have raised a few questions. Due credit and gratitude must be given to all who spoke and wrote against mass production following the Modi flare. Yet akin to the questions raised in Walter Benjamin’s The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, such unfortunate situations have raised many questions on what should indigenous communities do with their traditional attires/arts/crafts/aesthetics in the age of mechanical/digital reproduction; how to resist or cope up with the waves of cultural globalisation and so forth. Or would the new phenomenon annihilate art itself thus culture if it gets dissociated from its historical and traditional underpinnings that are ontologically fundamental to the very being of Luirim Kachon and the culture that nurtures its sustenance? Indigenous peoples are hard-pressed. Simplistic misunderstanding of culture and poverty of philosophy among the deniers of truth could be the root cause for these counterclaims which may gradually but will eventually un-conceal itself as the debate unfolds.

Origin of the Work of Art

Art is historical and as historical, it is the creative preserving of truth in the work… Art is history in the essential sense that it grounds history, argues Martin Heidegger in The Origin of the Work of Art. According to him, Origin here means that from which and by which something is what it is and as it is. What something is, as it is, we call its essence. The origin of something is the source of its essence. The question concerning the origin of the work of art asks about its essential source… the work first lets the artist emerge as a master of his art. The artist is the origin of the work. The work is the origin of the artist. Neither is without the other. Nevertheless, neither is the sole support of the other. In themselves and their interrelations, artist and work are each of them by virtue of a third thing which is prior to both, namely, that which also gives artist and work of art their names – art. He further argues that art in itself is thing-ly, work-ly, equipmental, symbolic and so forth. Arts-in-themselves and arts as they appear are in-detachable from each other and indispensable from the essence of truth. The significance of the essence of truth is also found in his magnum opus Being and Time and On the Essence of Truth. Nature of the argument in The Origin of the Work of Art is typically circular.

To understand Tangkhul Naga aesthetics, like any other pursuit, it is imperative to ask a few ontological questions before the investigation goes into the details of it: What do Tangkhul Naga aesthetics tell the community about itself? What does the Tangkhul Naga heritage tell the external world about the community and its aesthetics? What do such aesthetics do to the community? What is its significance? What is the essence of it? What purpose does it serve in the lives of Tangkhul Nagas? What does it say of the origin of Tangkhul Nagas and its identity?

One may note that, in the Tangkhul Naga Community, culture is substantially fundamental to aesthetics. Or, Tangkhul Naga aesthetics is accidental to its culture, customary practices, and traditional arts and crafts. In other words, Tangkhul Naga traditional art is a union of Tangkhul Naga culture and aesthetics. In this particular case, Luirim Kachon is a union of Tangkhul Naga culture and aesthetics. This may be better understood as ‘the union of substance and accident in Aristotelian conception of the kernel in an oak tree’. Customary practices, traditional arts and culture are again accidental to the Tangkhul Naga lifeworld and its worldviews. Thus, Tangkhul Naga aesthetics are not merely what met the eyes but delve way deeper into belief systems and the cosmos. Cosmology is altogether required to understand the cosmos of the Tangkhul Nagas for that matter Hill Peoples in Manipur which asks for transparency and accountability in the administration and operation of Manipur University and Indira Gandhi National Tribal University – more space for Hill Peoples in Universities within Manipur is a prerequisite. It requires the support of University, or Multiversity if one fancies a newer concept, to be researched, nurtured and sustained.

History and the Origin of the Work and Art of Luirim Kachon

Narratives surrounding the origin of Luirim Kachon are many and are evidently swayed towards the mitochondric valley of the state. In an unequal power dynamics, hermeneutics too favour the dominant culture to interpret to fit into their narratives and political agenda to their advantage and thus, igniting a war of cultural politics while lack of literature due to the intrinsic hide (oral) culture of the minority groups has not helped either in their attempts to claim what are rightfully theirs or their aspirations for cultural renaissance. However, in its rich folklore, myths and legends though scantily recorded as literature, there is a range of narratives of Luirim Kachon and how it began to disseminate to the valley, which is believed to be the abode of the younger brother, whose elder brother remained in Hungpung Village.

According to Dr Sinalei Khayi, legends had that Nongda Leirel Pakhangba (33 AD) undertook an expedition towards the hills as a part of a peace mission following a conflict between the hill and valley. The Chief of Hungpung, known as Hundung to the valley, threw a lavish reception upon his arrival and accorded his guest with a gift of Luirim Kachon. Mission succeeded, peace restored and satisfied with the gift of honour, Pakhangba re-christened the name at least for the valley as Leirum Phee – leiroom as living together and phee as cloth – as a pledge to be used by all the Meiteis, rich and poor alike at the time of marriage to signify the very meaning of ‘leiroom’ as coming together to live as one. “This account is reinforced by the oral collection of two octogenarians YL Vangam from Hungpung, and Stephen Angkang from Lungphu village in 1995 explicitly narrating the Legends of king Pakhangba” as narrated to Dr Sinalei Khayi. According to Khullem Chandrasekkhar (1975), the 12 century Constitution known as Loiyumba Shinyen also records that the Thingujams, one of the Sageis of the 7 Salais, are known to be the weavers of Leirum Phee, who are also said to be of Hungpung origin.

Dr Achan Mungleng and Dr Sinalei Khayi reiterated the significance of age-old folklore of the Tangkhul Nagas surrounding the romance of Nongpok Ningthou and Panthoibi. Nongpok Ningthou, a Tangkhul prince, was in love with Panthoibi, a Meitei girl. Their courtship was objected to by Panthoibi’s parents, who married off Panthoibi to Khaba. However, Nongpok Ningthou in an attempt to rescue their pristine love arrived at the groom’s residence and eloped with Panthoibi. As a prince, it was only natural for Nongpok Ningthou to wear Luirim Kachon as it is traditionally worn by kings and chiefs of clans as a shawl of honour like a crest in other cultures or modern times. In the process of elopement, Nongpok Ningthou offered his Luirim Kachon to Panthoibi to wrap her belongings. Thereon, this eventually became a cultural practice among the Meitei community during weddings where a replica of Leiroom Phee is used to wrap the Phiruk; it is to signify the strong relationship of Nongpok Ningthou and Panthoibi. This narrative finds reaffirmation in Dr Sinalei Khayi’s interaction/interview with Muttua Bahadur on 7.2.1996 and Dr Lokendra Arambam on 18.7.1996 during her fieldwork for her PhD thesis titled Arts and Craft of the Tangkhuls: A Study in their Cultural Significance. This narrative is said to have taken place during the reign of Kaangba.

Yet another narrative, the transmittance of Luirim Kachon to the Meitei came through the Angom community. Angoms are claimed to be descendants of Hungpung village as is also argued by Sobita Devi (Unpublished Thesis, 1991). According to this narrative, Luirim Kachon was first gifted to Nongmoinu Ahongbi, an Angom princess, by her parents on her marriage to Khui Tompok (154-264). What is interesting here is that in the tradition of Tangkhul Nagas, weaving is a collective traditional skill and art which no individual could claim ownership over at any cost. Thus, by this logic, as Angoms are of Hungpung origin, the claims put forth by Naoroibam Indramani that Angoms are the owners of Luirim Kachon is null and void. Despite the differences in the narratives, what is common to all the narratives is that dissemination of Leirum Kachon to the valley began from Hungpung village.

Colonial Accounts

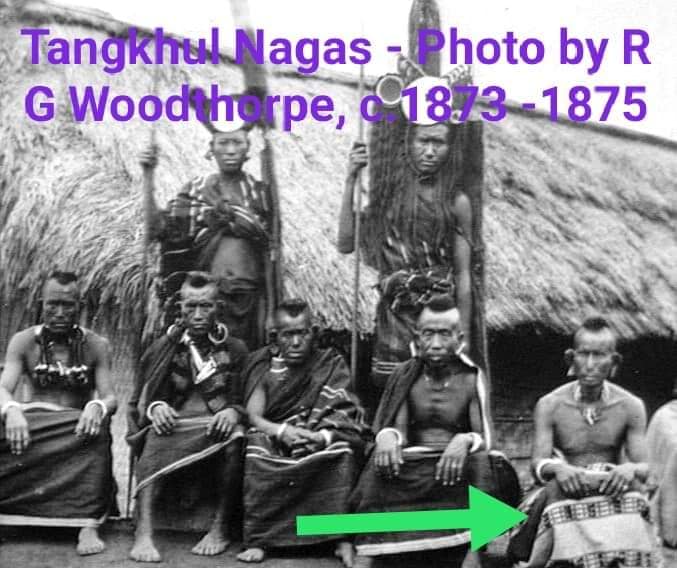

Robert Gosset Woodthorpe (1844-1898), a British officer as an Assistant Superintendent with Survey of India and an amateur artist, firstly began his work in the Luishai Hills. He then went on to the Garo Hills and Naga Hills; was engaged in Surveying the Nagas. According to the British Museum website, “His (Woodthorpe’s) 1882 lectures on the Nagas remained a standard work for many years; he illustrated his own writings with some fine drawings”. “He (Woodthorpe) became renowned as an expert on India’s frontiers, giving talks on his travels to prestigious London-based learned institutions including the Royal Geographical Society and the Anthropological Society of Great Britain and Ireland” opined Thomas Simpson, University of Cambridge (2019),. His ethnographic photographs of Tangkhul Nagas (1873-75) and sketches recorded in his diaries titled Naga Hills (1876) still stand to this day as living documents.

Despite all these evidence and historical records from colonial accounts, of late but unlike in the past, there have been counter claims from the Meitei community regarding the ownership of Luirim Kachon. Now that it has been successfully brought home, it now is a classic case of neighbours engaged in a riff after an external intrusion had Debeen successfully fended off.

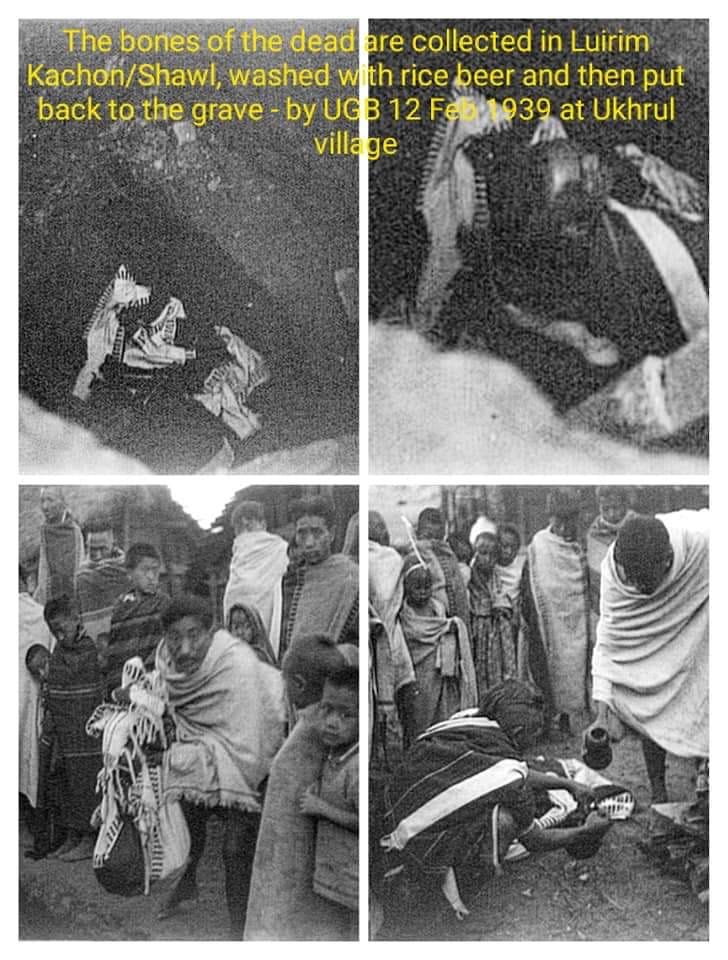

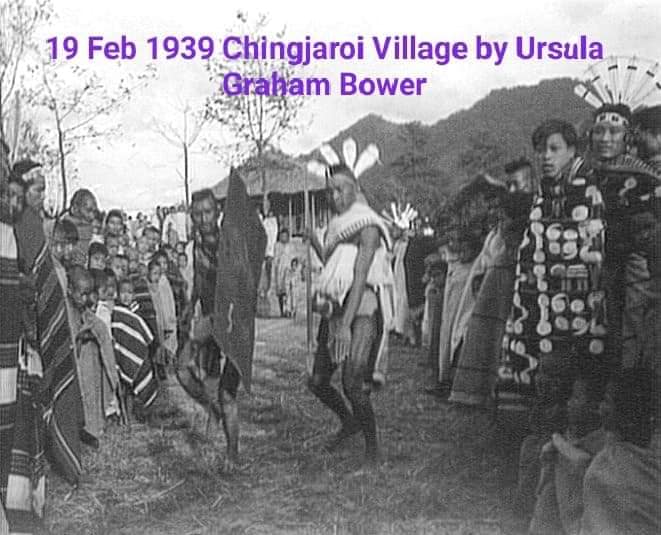

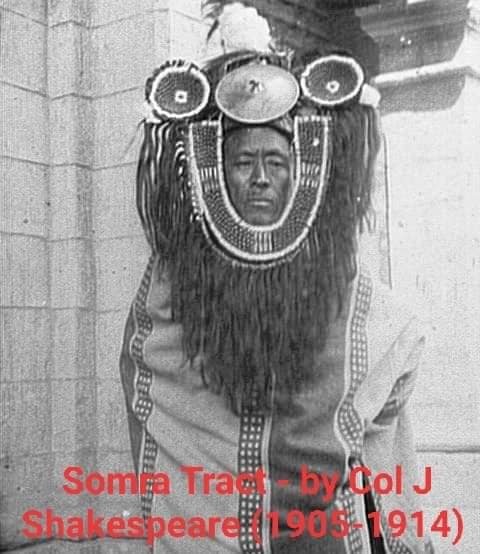

Colonel John Shakespeare’s ethnographic photographs and as also recorded in Julian Jacobs’s The Nagas: Hill Peoples of Northeast India (1998) cover numerous villages from the extreme north of Somra village in Myanmar to Bungpa Village, of which the former Chief Minister of Manipur, Rishang Keishing is a resident of, in the east and Ukhrul (then a village) and Ramva village in the centre. Also, Ursula Graham Bower’s photographic artwork of the Tangkhul Nagas, which are widely circulated including in Julian Jacobs’s The Nagas: Hill Peoples of Northeast India (1998), museums and archives, and wherein Tangkhul Nagas are vividly seen draped in Luirim Kachon, explicitly connote the popularity of Luirim Kachon among the people. The photographs depict the place of the significance of Luirim Kachon in the custom, tradition and culture of the Tangkhul Nagas; like the particular Chingjaroi village series wherein the ritual of wrapping bones of the departed and so forth could be seen. In Naga Path, Ursula Graham Bower also wrote: “…the broad-banded scarlet-and-white clothes which the Tangkhul Nagas wore.”

Despite all these evidence and historical records from colonial accounts, of late but unlike in the past, there have been counter claims from the Meitei community regarding the ownership of Luirim Kachon. Now that it has been successfully brought home, it now is a classic case of neighbours engaged in a riff after an external intrusion had been successfully fended off.

Noteworthy is the solidarity between the Hills and Valley to resist such an intrusion and attempts at cultural misappropriation. Mutual understanding and amicable settlement of the issue is the only way forward to retain the cultural relationship among the two communities as the hills and valley are not independent of each other but complementarily reinforcing each other. For there are the Hills, there is the Valley; for there is the Valley, there are the Hills. Quoting Dr Sanajaoba “a Meitei family without Naga custom cannot be called a Meitei, and a Meitei Laiharaoba without Nagas part can never be performed” (North East Sun, Dec. 31.1994 – Jan 6.1995), Dr Sinalei Khayi also argued that due recognition of ownership and mutual respect are inevitable for peaceful and harmonious coexistence; and continuance of mutual cultural exchange.

II

Religio-Cultural Embeddedness

So far, the arguments and counter-arguments are made only from a historical perspective until the devious advent of political economy perspective lately. Most have failed to consider the cultural elements or have only mentioned the cultural elements in passing. Cultural aspects must be researched upon and debated as culture is not a standalone entity. In other words, culture is coterminous or overlaps with history especially in the indigenous lifeworld. Thus, a discourse on Luirim Kachon without the cultural aspects is incredulous. Luirim Kachon, in the context of Tangkhul Nagas like any other shawls or artworks, is a work of art sanctified by the sacrosanct hand-virtues of nimble fingers possessed only by the womenfolk and handed down from the mother to daughter experientially at situated space and time. In other words, Luirim Kachon as a traditional art is a union of Tangkhul Naga culture and aesthetics where culture is substantial to the aesthetics while aesthetics is accidental to the culture.

According to Dr Sinalei Khayi in her article titled Ownership of Luirim Kachon, Ukhrul Times, “Those entitled with the honour of wearing the shawl are the ‘Khayaiwo’ (chief of chiefs), Awunga (village chief) and eldest of clans and lineage (Amei kharar) which ultimately constitute the ‘Hangva’, the highest body of the village. This shawl, therefore, naturally becomes the dress code of the hangva, the highest house of Tangkhul village, Hangvashim. Usage of the shawl, however, is also entitled to the person who performs the feast of merit, ‘marankasa’ (construction of carved house, erection of genna post, pulling of log bed called bedkhok). The shawl is used in performing rites & rituals like wrapping the bones of the dead while recycling the old burial site (as depicted in Ursula Graham Bower’s Chingjaroi Village series); to honour the death by covering the body or the coffin; a prestigious gift by the bride on marriage; used as a display of wealth in the exhibition of the feat (otrei kasa) during harvest; and also to marked the feast of merit”.

Likewise in customary practices and culture of Tangkhul Nagas, one observes Whiteheadian aesthetic ontology as Tangkhul Naga aesthetics capture the essence of reality that is the lifeworld and worldviews. Also, Tangkhul Naga aesthetics adhere closer to RG Collingwood’s conception of magical art than amusement art; since Tangkhul Naga aesthetics revolve around its interaction with the reality as in culture and with their lifeworld and worldviews as in cosmology, but not merely as forms of amusement to escape from reality momentarily. This claim is sensible owing to a truth that Tangkhul Naga aesthetics are historical, contextual and are continuous streams of consciousness (read as the oral and experiential transmission of knowledge and intuitive experience) that evolve with time and spatial nature. Moreover, Tangkhul Naga aesthetics incline more towards aesthetic moralism than autonomism since it is a presentation and representation of culture where morality as virtue and art/aesthetics are not independent of each other but are interdependent and complementary. The ontological function of Tangkhul Naga aesthetics is to bridge the gap between the realities/truths and lifeworlds/worldviews with the presentation (and representation perhaps) of it. In it, there is Heideggerian aesthetic experience, which is also to say that there are a priori elements that cannot be circumscribed within the cognition of empiricism or positivism. A priori herein is religio-cultural embeddedness.

Underneath the veil of cultural politics, there lies the Heideggerian conception of Aletheia, which is the unconcealment or the truth as a rift from the strife between the earth and the world; the Alethia of or to Luirim Kachon is in the work-being of the work of art of the production of Luirim Kachon which is a traditional art owned collectively by the whole community and not individuals; the Alethia is in the equipmentality of Luirim Kachon in customary rituals and its significance in wrapping the bone remains of the departed, ‘August occasions’ including Maran Kasa (feast of merit) and so forth; the Alethia is in its symbolism as a shawl of honour, prestige and merit embedded in the cultural mores and as symbolic gifts to dignitaries. These fine thingly-characters of Luirim Kachon in coherence with the essence of truth is the essence of Luirim Kachon. Here I am talking about that essence of eromba and hoksa that is intrinsic to the identity; that eromba-ness which cannot be dissociated from the Meitei-ness is that Luirim-ness which cannot be detached from the Tangkhul Naga-ness.

Being Didactic is Dialectical

If discourse is didactic, there is an indication and significance of the presence of dichotomies as teacher and pupil, strong and weak or dominant and marginalised. If discourse is dialectical as in the Hegelian dialectics of master and slave, it is a well-proven debate that there is a displacement of discourse and hidden transcripts where the seat of dominance is retained for the masters at the cost of the marginalised section rather than a desirable synthesis that is inclusive of the latter too. That didactic and dialectic methods have been debunked, dialogical methods of engagements with every stakeholder as equal partners have proved to be more effective like the performance of the present government has proved to be better than the previous government in terms of peace, liaison and bonhomie among the communities.

Whoever contempt the assertion by Tangkhul Naga Long to claim their cultural rights to ownership over Luirim Kachon and its design, as identity politics targeted at corrupting the integrity of Manipur, too must have the heart, mind and intellect to point out the politics surrounding the Fourth Delimitation Commission; that unequal representation of the valley and the Hills at the State Assembly is ruining the political fabric of Manipur. Also, reverse migration at the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic exposed something unpleasant more than the chaotic rehabilitation of the returnees. Much like the step-motherly treatment given to the Hills in the Healthcare Sector even during this pandemic, it also raises the question of why there was so much migration from the Hills outside the state. Never mind the theory of natural selection, adept adaptation away from the state might have debunked the concept of survival of the fittest in social Darwinism. Valley hegemony has pushed many Hill Peoples to the margins or outside the state; the latter has sparsely been a blessing in disguise for some, especially educational migration which has exposed the Hill Peoples to a better education system outside the state. If in-breeding is ruining the likes of Allahabad University as per reports in The Print, lethargy due to lack of competition from the Hill Peoples, who have been structurally kept out, would kill the universities in Manipur. To selectively go blind on such exigencies is rather to miss the forest for a tree.

It is pertinent here to recollect the narratives of ‘splitting the baby’ or ‘cutting the baby into half’ in the Solomonic judgement or ‘tug of war’ between a mother and a Yakshini over a baby in a Jataka story wherein the sage Mahosadha, who reincarnated as Buddha, presided over the adjudication. In this particular case of Luirim Kachon, one is able to make slanderous statements without any remorse using derogatory analogies and metaphors like the non-mother who fought for or Yakshini who pulled the child relentlessly to prove her loyalty at the perils of the child. A perusal of a certain article titled Not Just a Piece of Cloth: Cultural Politics of Leiroom Phee and Beyond in The North-East Affairs clearly shows that the author failed outright in emotion test by absurd procedures at the choice of certain analogy to reduce a traditional art of a community and hand virtues of nimble fingers of the womenfolks to mere derogatory analogy; it is not only disrespectful but indicative of indecency and arrogance, which could only be seen in the disposition of an impostor or one out with an ulterior motive of distorting history. The hypocritical concern is easily exposed in the choice of words and analogy and only a preposterous claim would choose such a language, which effectively proves one’s false claims. Why does it have to be true that principles, integrity and honour are a matter of cultural values that such is only common in a few but uncommon in some?

If it is a mere novelty without its roots in Leiroom Phee, it is without its historico-cultural essence. However, if it has its roots in Leiroom Phee, it has historico-cultural relevance and the essence of truth as Leiroom Phee has its roots in Luirim Kachon. It is a fruit of mutual cultural exchange, as is also argued by Trishna Wahengbam, without any intent for misappropriation. Yet the counterclaims of recent have come in with other ulterior motives.

Divorce is Myopically Nihilistic thus Culturicidal

Shimreiwung Zimik (Doctoral thesis, 2009) argues that artworks are more than its utility and aesthetic appeal. To quote: “In societies that have not adopted modern technology, the works of handicrafts have various ritualistic significance, and thus an object that goes beyond the utilitarian aspects”. This ‘various ritualistic significances’ signifies that art and crafts, Luirim Kachon in this case, are phenomenologically situated, cultural and historical besides its teleological utility and aesthetic appeal. Should a new design be created by ignoring the various ritualistic significance and other cultural relevance, such a novelty would be baseless, rootless, unfounded and unfortunate. If it is to be a collective symbol of the state, it is imperative that it be of some historical and cultural relevance that cohere with the identity of the peoples. If it is a mere novelty without its roots in Leiroom Phee, it is without its historico-cultural essence. However, if it has its roots in Leiroom Phee, it has historico-cultural relevance and the essence of truth as Leiroom Phee has its roots in Luirim Kachon. It is a fruit of mutual cultural exchange, as is also argued by Trishna Wahengbam, without any intent for misappropriation. Yet the counterclaims of recent have come in with other ulterior motives.

As thereby we have deduced, this collective symbolic ‘not just a piece of cloth’ is, in fact, cultural in its aphor (plaits), chontheira (tuft or dangling threats), patterns, colour combination and other intricate designs only that its due ownership is being refused to the rightful owner. Refusal of ownership will ensue the beginning of the rootlessness of the collective symbol of Manipur. This reminds one of what Martin Heidegger had said of the rootlessness of the Western thought: Roman thought takes over the Greek words without a corresponding, equally original experience of what they say, without the Greek word. The rootlessness of Western thought begins with this translation. Also, if, according to Martin Heidegger, the origin of something is the source of its essence, the essence of Luirim Kachon is in the religio-cultural embeddedness and that of Leirum Phee is in the ‘living together’; the mutual cultural exchange between Tangkhul Nagas and Meitei community which later find reflection in cultural practices such as Pham Konba in Meitei weddings, Lai Haraoba and Meira-Haochongba. Any misappropriation is in itself an act of nihilism. A thing devoid of culture and history is not a thing but a new thing with a rootless base, without its essence. Like a Luirim Kachon without its essence is no longer a Luirim Kachon, a Leiroom Phee without its essence is no longer a Leirum Phee. Without the essence of Leiroom Phee, cultural practices such as Pham Konba, Lai Haraoba and Meira-Haochongba become meaningless. As argued by Walter Benjamin in The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, it definitely is nihilistic, herein culturicidal. If the valley is serious about Sanamahi Renaissance, fanning culturcide is myopic; as its revival is unlikely without historical and cultural backgrounds which are intrinsically relative. Sanamahism is also talking about a different lifeworld and worldviews based on the essence of truth distinct from the dominant West, who would demand positivist approach; essentialising ‘standards of proof’, ‘explanatory precision and predictive certainty’, to validate the claim for a renaissance.

All ethnic groups in the state of Manipur, by extension the entire Northeast India, are genetically minorities. Whoever may claim to be the dominant group or the winner of ethnic clash, all yet becomes a minority beyond the border of Manipur (Northeast India). Pessimistic Machiavellian statecraft built on insecurity regardless of its strategic foresight will not bring peace to the state of Manipur. Peace is a possibility with dialogue. Glimpses of peaceful coexistence are evident in the last couple of years though far from satisfactory. All it took was dialogue, recognition and mutual respect. If peace is a possibility, unity too is; for unity and peace are bound together by an altruistic fraternity. All communities have undergone their share of good times and bad times at different spaces and times. However, the time has come for all thinking citizens to ditch the colonial divide and rule policy but bat for a unity wager akin to Pascal’s wager; all but unity is the best of all possible situations in the long run.

The author is a Research Scholar at the Tata Institute of Social Science, Mumbai (The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of The North-East Affairs)